Armed Conflict

As a direct victim of the conflict, going through all these experiences at such a young age and without knowledge of the subject, I could only say at that moment that there were "bad men" who wanted to harm us and end our innocence and peace. This created in me the questions that drove me to search for explanations and truth."

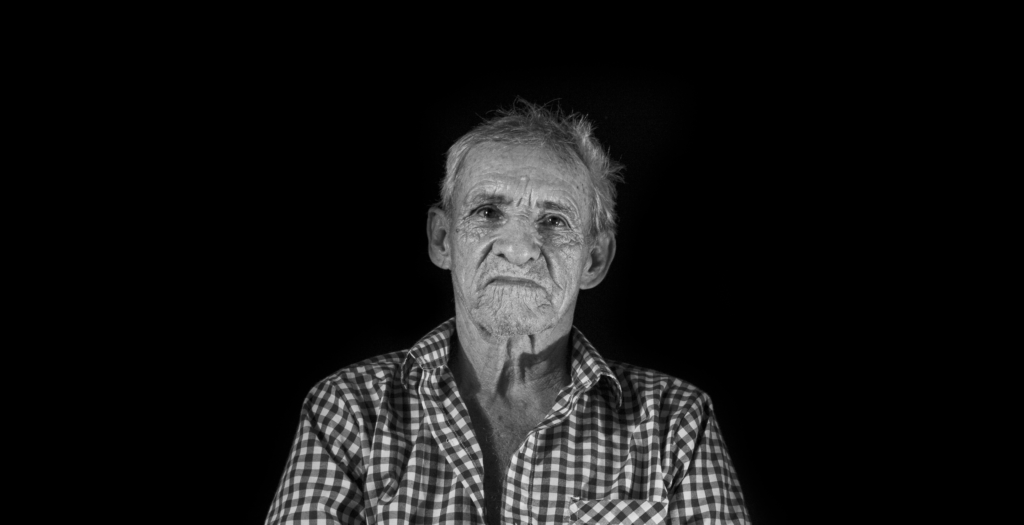

–Manuel Balaguera Peñaranda, Co-Founder

Colombia has been in an almost perpetual state of conflict since it gained independence from Spain in 1811. Perpetually mischaracterized as a narco-conflict; colonialism, independence, neocolonialism, and the ideological affinities that emerged from them set the foundations for decades of violence in Colombia. Land has always been at the conflict’s center. Power disparities established by colonial practices presented campesinos with significant barriers to land ownership. The campesinos clashed with landowners and the central state, who they felt prioritized the interests of the property-owners. As they began to mobilize, both Liberal and Conservative elite interests were threated.

In the 1940s, presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitan won the favor of many campesinos due to his support of economic redistribution and promise of increased political participation for disenfranchised rural communities. His assassination in 1948 sparked riots, protests, and violent clashes now known as ‘El Bogotazo’ and ‘La Violencia’. Threatened by the unrest, elites from both sides united to form a power sharing agreement called the Frente Nacional, effectively excluding other political party and strategically delegitimized an increasing number of communist groups. Without a means of political expression in Bogota, communist supporters turned outside of the city for support. Pedro Antonio Marin (nom de guerre: Manuel Marulanda) and Luis Alberto Morantes Jaimes (nom de guerre: Jacobo Arenas), for example, unified the grievances of rural farmers in region known as Marquetalia.

Fearing the development of a Cuban-style revolutionary situation, action against communist enclaves were considered essential to Colombian national security. With this in mind, Colombia developed Plan LAZO drawing on the recommendations of United States post-Cuban Revolution counterinsurgency strategy. Aiming to eliminate independent communist republics, 16,000 Colombian troops, backed by the US, attacked the communist enclave of Marquetalia . Survivors, led by Marulanda and Arenas formed Las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the Colombia – People’s Army, or the FARC) . This marked a fundamental shift away from self-defense to all-out revolution. The occurrences at Marquetalia galvanized unification, and the formation of a more cohesive, structured ideology.

The first decades of the FARC’s existence were characterized by traditional guerrilla warfare and expansion into remote areas throughout rural Colombia strategic to waging war with the Colombian military. The late 1970s however mark a turning point. They found massive financial opportunity through kidnappings and participation in drug trade. This territorial expansion included the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

Two guerrilla takeovers took place in the township of Minca, the first in 1988 when approximately 160 guerrillas arrived in the town. They forced the seven police officers on duty to surrender, and kept them captive in camps up the mountain for two weeks. The guerrilla returned to take over the town a second time in 1998. By then, co-founder Manuel was old enough to remember.

"At a young age, I had experiences that marked my life forever.

One of the first was the second guerrilla takeover by the FARC-EP. They arrived at around 9:00 at night. My family was spending time together suddenly the power went out and, wanting to know if it was just our house or the whole town, we looked out the nearest window and saw several groups of guerrillas spread out in a flat area next to our home.

One of the moments of terror was hearing the loud sound of the bullets for the first time. We immediately ran to hide under the mattresses, which in reality, was more psychological safety than anything else, since a stray bullet would have penetrated our makeshift mattress shield with ease.

During that long night we were able to hear gunshots, bombs and guerrilla chants. My father, who was closest to the police station with my older brother, says that he was protecting my brother with mattresses and his body. He felt like the bullets were hitting the wall, but he couldn’t find a good time to escape. They waited there all night.

At dawn we faced the reality of the result of this guerrilla attack. Even as a child, I remember that battlefield. There were no bodies, but we could see wells of blood and trees on the ground. The constant shooting during that long, sad night, left a fatality in the community, houses wiped off the map and a police station almost completely destroyed.

The fear that consumed Minca at dawn was worsened by the fact that the police left the town and there were rumors that the guerrilla were still around us. Almost all of us Minqueros were displaced to Santa Marta or Barranquilla. The town was practically abandoned.

As the FARC increased kidnappings and participation in drug trade, they began to pose a very serious threat cartel members, landowners, and elites–those whose families and power were most likely to be targeted. These self-defense groups began to work with the Colombian army to neutralize the guerrilla, underpinned by a counterinsurgent mentality.

In 1997 multiple paramilitary groups consolidated into one group: The Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) and expanded territorial control into regions with guerrilla presence. While all groups were extremely violent, the paramilitary actions surpass all other groups combined in terms of number of deaths and brutality. Nearly all paramilitary killings during this period were of civilians, which occurred three to seven times as often as those committed by the FARC who, beyond engaging in direct battles with guerrilla groups also massacred and killed suspected guerrilleros, and their sympathizers. Unlike FARC, the AUC is not engaged in conflict with the national government. Financed through narcotrafficking, extortion and forced land takeovers, these groups evolved into paramilitary units, and consolidated significant economic and political power.

The formalization of the AUC and their state-sponsored war against the guerrilla groups from the late 1990s until the early 2000s marked an uptick in violence and displacement across the country. In 1997 multiple paramilitary groups consolidated into one group: The Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) and expanded territorial control into regions with guerrilla presence. While all groups were extremely violent, the paramilitary actions surpass all other groups combined in terms of number of deaths and brutality. Nearly all paramilitary killings during this period were of civilians, which occurred three to seven times as often as those committed by the FARC who, beyond engaging in direct battles with guerrilla groups also massacred and killed suspected guerrilleros, and their sympathizers.

The Sierra Nevada became contested territory. The guerrilla and multiple paramilitary groups fought over control of the region. In the early 2000s, thousands of people were displaced, killed or disappeared in the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta.